Harper's Bazaar: How Fashion Legend Bonnie Cashin Broke into Bazaar

February 25, 2025 – Lynsey Cawdle

HOW FASHION LEGEND BONNIE CASHIN BROKE INTO BAZAAR

Close friend of American designer Bonnie Cashin remembers her indomitable spirit.

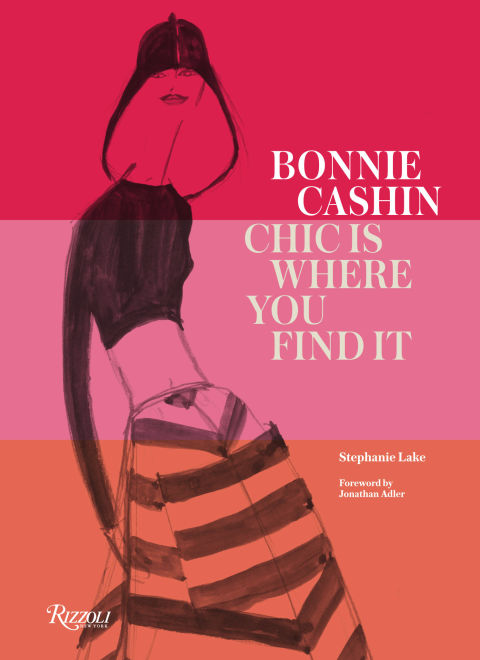

Bonnie Cashin was one of America's pioneering designers, widely credited for spearheading New York's presence in the Europe-dominated fashion industry when she burst onto the pages of Harper's Bazaar in the 1930s. Scholar Stephanie Lake, author of the new biography Bonnie Cashin, Chic Is Where You Find It (Rizzoli) and a close friend of the designer's, remembers her indomitable spirit.

Harper's BAZAAR: How did Bonnie get her start in the fashion world?

Stephanie Lake: Before she worked in fashion, Bonnie designed costumes at the Roxy Theatre in the 1930s. It was a huge job. She would churn out thousands of costumes for the dancers, who rivaled the Rockettes, but what she really wanted was to work in fashion. So she took matters into her own hands, and created a show at the Roxy where the stage was a life-size Harper's Bazaar spread, a magazine come to life. And all the dancers would appear to walk off the pages in clothes of her designs—real life clothes, not stage clothes. It was basically a guerrilla fashion show, in 1937. The Roxy was a high-profile theater, and there was nothing more opulent.

Carmel Snow [Bazaar's newly-minted editor in chief] heard about the show and came to see it, and she immediately decided that Bonnie should be a fashion designer. Bonnie had no experience or credentials, but Snow put her in contact with Louis Adler, who was a huge force in fashion and had a very prestigious dress and coat line. Snow took Cashin to his office and said, "Here's your new designer." She was suddenly put in charge of creating ready-to-wear, and she had absolutely no idea what she was doing. She tried to adapt things from stage to sportswear; the pattern makers thought her designs were impossible, but she had her mother by her side, who would make samples to prove that things could be done the way Bonnie wanted them.

Snow's endorsement landed Bonnie a top job in fashion. You can scale it down to that, basically. It goes back to how important Bazaar is, and what it represents. The magazine had an appreciation for modernity and for the change that was happening across the arts in general during that time.

HB: How did you become close to Bonnie?

SL: I first met Bonnie when I was in graduate school. She was a force—just so engaged with every single moment of her life. Her sense of wonder was limitless and contagious. She made me interpret the world in an entirely new way.

In creating her biography, I completely underestimated what would go into compressing her story into these 300 pages. She had two apartments in U.N. Plaza and I have the contents of both of them. Bonnie kept a personal design archive, so I maintain nothing less than a private museum, and I do everything I can to share and get the much-deserved recognition for everything that she's done. It is not only the iconic designs but also a record of how she worked. I have all these little scraps of paper—she would write little notes to herself, come up with the name of a color she wanted to use before the color even existed.

HB: When did Bonnie's clothes first appear in Harper's Bazaar?

SL: Her designs appeared as early as the spring of 1937, but in 1940 the magazine did the very first issue that didn't cover clothes from Paris because of the war. There's an editor's note that says, "Introducing 7th Avenue Designers," and Bonnie was the first one photographed and the first one mentioned, which is an incredible moment. It was a pivotal point in fashion, right after Diana Vreeland was brought in [as the fashion editor at Harper's Bazaar]. Carmel Snow was obviously a fantastic scout for talent. It was an incredibly exciting time for American design and American sportswear, and the fashion industry was opening up and moving from Paris. The magazines weren't just covering Paris couture and high society. There was a changing of the guard and Bonnie was part of it.

HB: What was her relationship like with Diana Vreeland?

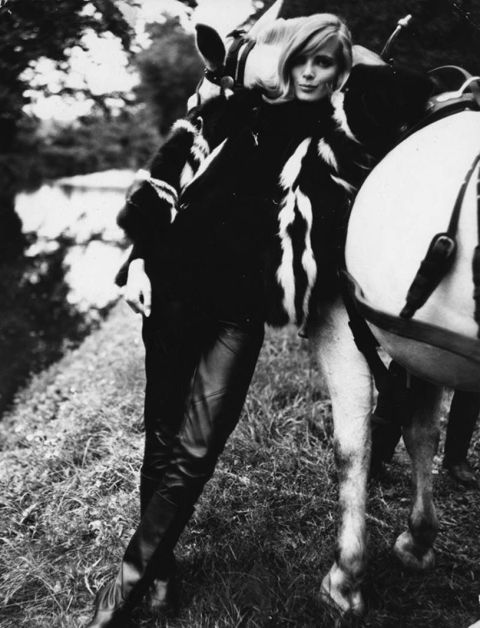

SL: I have some of Vreeland's notes to her, written in almost unintelligible script. Of course, Vreeland was another exuberant, iconic woman. I think they recognized in each other the same spirit, the same boldness, the same sense of joy and also frank disdain. They were incredibly forthright and strong, and so they had a very warm friendship. The letters went back and forth. I have one from Vreeland that says, "The world is leather mad, and of course, you've always been the best and the first." She was always very ready to give Bonnie credit for what she had contributed to fashion. Bonnie didn't have the same sense of drama that is so fantastic about Vreeland, but at their core, I think they were very similar. It's just in their outlook and their sense of possibility and also in the sense of having control, and having great confidence in what they were doing. Bonnie was unflinching. She never had an investor. She was never an employee. She never licensed. She didn't have assistant designers. She was the sole creator of her work, and she succeeded in all of those decades, staring in the 1930s and not retiring until the mid-1980. She worked independently from her own studios in her homes. It's almost impossible to fathom that one could do that, especially today.

HB: In what other ways was she a pioneer?

SL: In the mid-century, she decided that her name was going to be on everything that she designed from that point on—no investors. She set up her independent studio and gave a few shares to her mother. That was the whole company. No one else was ever a part of it. It's so inspiring, that integrity. Women's Wear Daily would cover how she was structuring her company, and how radical it was. Everyone was very wary of her, and to be a single woman in that era—she wasn't married, she didn't have children—defied every convention. But she never considered anything a struggle, she just saw the possibilities.

Bonnie Cashin: Chic Is Where You Find It, by Stephanie Lake, is out now from Rizzoli.